The Kurdish Question on the Map

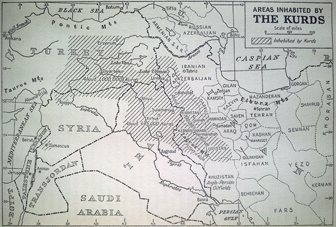

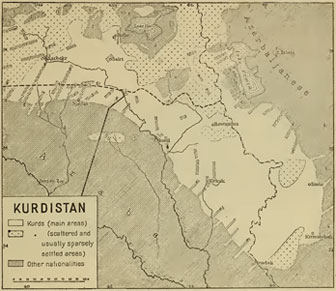

Often described as one of the largest national communities in the world without their own state, the Kurds, numbering somewhere between 25 and 30 million, are a very distinct community, with its own language, history and traditions. Nonetheless, their ethnic identity has been for a long time denied by their major neighbors, the Arabs, the Turks and the Persians. Without their own state, the Kurds have seen the Kurdistan, “the land of the Kurds”, divided mainly between these neighbors (the present-day states of Turkey, Syria, Iraq and Iran).

The Golden Age of the Kurdish history is placed in the 12th and 13th centuries, during the Ayyubid dynasty, a Muslim dynasty centered in Egypt, founded by the most illustrious Kurdish national, Saladin. Territorially, the small Kurdish principalities and tribes have been part of the various Muslim empires (Abbasid Caliphate, Safavid Persia, etc.) and most of the Kurdish lands have been finally annexed by the Ottomans in the 16th century. Some smaller parts (in Caucasus and Central Asia) have been occupied by the Russian Empire in the 19th century and others remained under Persian sovereignty.

After centuries of foreign domination, the Kurdish communities in the Ottoman and the Persian Empires have expressed a surprising cultural and political regeneration at the beginning of the 20th century, after the First World War.

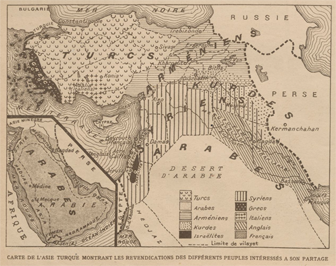

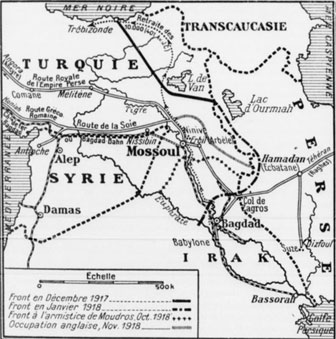

The defeat of the Ottomans in the WWI had already opened the way to the disintegration of the Ottoman multinational state. Furthermore, the Great Powers’ interests in the Middle East, the Armenian genocide and the anarchy caused by revolts and revolutions in the Caucasus had to seriously affect the political equilibrium in the region. In this context, all of the major non-Turkish nations of the Ottoman Empire (Arabs, Armenians, Assyrians, Pontic Greeks, etc.) have demanded the establishment of their own national state and, naturally, the Kurds did not constitute an exception.

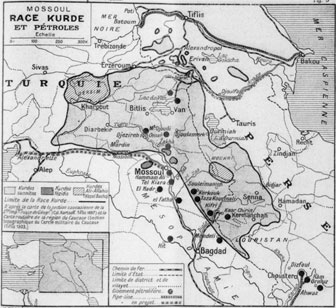

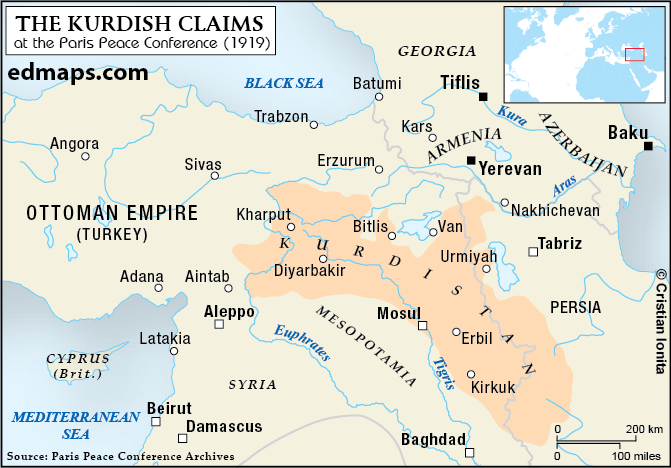

In 1919, at the Paris Peace Conference, the Kurdish delegates have formally claimed the constitution of a great Kurdish state within the ethnic borders of the main Kurdish homeland.

The Kurdish demands, based on the right to the national self-determination, have been contested by the Ottoman and Persian governments and by other national communities in the region (Arabs, Armenians, Assyrians). Tracing a clear and “right” demarcation line between the different ethnic, cultural and national communities was not really an easy political enterprise. In fact, the die was already cast: before the end of the WWI, France and Britain have already established the main lines of the new map of the post-Ottoman era of the Middle East area (the Sykes-Picot Agreement). Kurdistan was not on this map...

In spite of the Franco-British omission, the Paris Peace Conference of 1919-1920 has offered a chance to the Kurdish nationalists: between a larger and independent Wilsonian Armenia and the French and British mandates of Syria (and Lebanon) and Mesopotamia, there was a place to fill in for a small Kurdish entity.

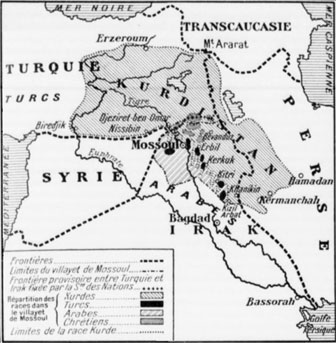

According to the Treaty of Sèvres (1920), it was accepted a local autonomy within the Turkish State for the predominantly Kurdish areas lying east of the Euphrates, south of the southern boundary of (the Wilsonian) Armenia and north of the frontier of Turkey with Syria and Mesopotamia.

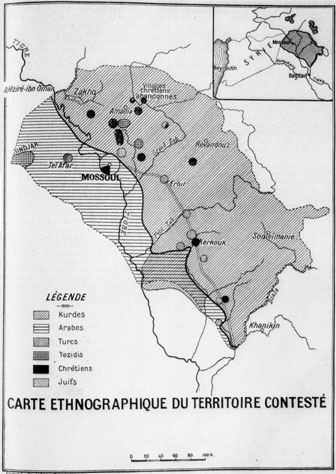

If within one year from the coming into force of the Treaty of Sèvres the Kurdish people within this Kurdish autonomous entity would have asked for the independence from Turkey, the Great Powers would have accepted the establishment of an independent Kurdish State. Furthermore, it was accepted too “the voluntary adhesion to such an independent Kurdish State of the Kurdish inhabiting that part of Kurdistan which has hitherto been included in the Mosul vilayet”.

Unfortunately for the Kurds, the Ataturk Reconquista put an end to the Kurdish dream. The Treaty of Sèvres has been annulled and the new Treaty of Lausanne (1923) produced results less favorable to the Kurds. In fact, Turkey didn’t recognize Kurdish aspirations for autonomy and the Kurds became “Mountain Turks”...

In Mesopotamia, after the establishment of an ephemeral Kingdom of Kurdistan in 1922 in the region of Mosul, the League of Nations awarded in 1926 this predominantly Kurdish territory to the new Iraqi State, with the provision for special rights for the Kurdish community. The Kurdish revolts of 1931-1932 and 1935 suggested that this demand hasn’t been respected by the Iraqi government.

Surprisingly, a new Kurdish territorial project had to be realized in the Soviet Caucasus. In Azerbaijan, in the Lachin corridor, a region between the Armenian borders and the Nagorno-Karabah autonomous region, the Soviet government established in 1923 a Kurdish autonomous district, a “Red Kurdistan”, in order to provide a national home to the Soviet Kurds. Dissolved in 1929, the Kurdish district was briefly succeeded by a Kurdistan region in 1930 (May-July). After the region’s liquidation, most of the Kurdish population has been deported. (Sixty years later, a new Kurdish state had to be established in the Lachin corridor, but, without a Kurdish majority, this Lachin Republic failed to survive as a Kurdish entity and has been finally annexed by Armenia.)

After the territorial fiasco of the 1920s and 1930s, a new Kurdish nationalist’s conception of a viable Kurdish state has been presented to the first session of the United Nations at the San Francisco Conference (1945). According to the Kurdish petition, Kurdistan stretched from the Mediterranean Sea to the Persian Gulf and included the predominantly Kurdish territory of the Turkish Eastern Anatolia, the Iraqi region of Mosul and the Western Iran. In addition, there was too some smaller Syrian, Armenian and Azeri territories to be annexed to the Kurdish state. If these demands had some rational arguments, the surprise was the Kurdish claim to the non-Kurdish Iranian region which had to offer an access to the Persian Gulf.

Anyway, the Kurdish State as claimed at the San Francisco Conference was never established. As always, the Great Powers’ interests prevailed and, in the context of the Cold War, the Kurdish demands for an independent national state have been neglected.

A last attempt to put a Kurdish state on the map is made in 1946. With the Soviet aid, an ephemeral Kurdish Republic is established in Iran, in the region of Mahabad. Once the Soviet support was gone, the puppet state succumbed under the pressure of the Iranian army.

After the WWII, the Kurdish nationalist organizations changed their major objective and, with regard to the Kurdistan’s territory, they opted for a lesser objectionable frontier. In order to reduce the possibility of a major conflict with other nationalist movements, the State of Kurdistan had only to incorporate the predominantly Kurdish regions of the Turkish Eastern Anatolia, the Northern Syria, the Iraqi Kurdistan and the Iranian Kurdistan, with an access to the Mediterranean Sea.

In Turkey, the most radical Kurdish organization, the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), waged from 1984 to 2013 an armed struggle against the Turkish government for political rights and self-determination for the Kurdish community. Finally, the PKK abandoned the demands for the unilateral establishment of an independent Kurdish state and opted for a “solution process” between the Turkish State and the Kurds.

In Iraq, the relations between the Kurdish community and the central government have known a very sinuous course after the WWII. After an initial repression and a first Iraqi-Kurdish War (1961-1970), the Iraqi government has accepted some political and territorial autonomy for the Kurds and established in 1970 a Kurdish Autonomous Region in the Northeastern Iraq. The collapse of the Kurdish autonomy constituted the main reason for a Second Iraqi-Kurdish War (1974-1975) and a Kurdish rebellion (1983-1988).

In 1991, after the Gulf War, a new Kurdish revolt challenged the Iraqi government and, a year later, the Kurdish nationalists will establish a Kurdistan Regional Government. After the 2003 invasion of Iraq, this autonomous Kurdish region became constitutionally a federal entity of Iraq, but its territorial structure was not definitive because the Iraqi government, the Sunni Arab and Assyrian political organizations, etc. contested the Kurdish territorial claims. However, in 2014, during the war against the “Islamic State” (DAESH), the Kurds took over much of the disputed territories.

In fact, the war against the DAESH has facilitated the territorial expansion of the Kurds autonomous entities.

In Iraq, the Kurdish government of Erbil controls almost all the territory the Kurdish nationalist ever claimed in Iraq (the Southern Kurdistan). However, the city of Mosul remained under the DAESH occupation and the Niniveh region is partially controlled by the Assyrian Christian militias.

In Syria, after some victories against the DAESH, the Syrian Kurdistan (Rojava) has obtained a Kurdish administration and a de facto autonomous government.

Not surprisingly, if for the Kurds the “liberation” of Rojava and Southern Kurdistan is the first phase of the national reconstruction, the neighbors saw this nationalist offensive as an illegal attempt aimed at the disruption of the national unity and territorial integrity of their states.

However, the establishment of the Kurdish autonomous governments in the Northern Syria and Iraq seems to be a fait accompli. The present-day Syrian and Iraqi governments don’t have the capacity to challenge the Kurdish control of Rojava and Southern Kurdistan.

In Iran, the central government succeeded to manage the conflict with the Kurdish insurgency, thanks to a stick-and-carrot approach, but the situation is different in Turkey. After the truce with the PKK, the Turkish government was confronted with some kind of hybrid nationalist political warfare. In June 2015, a Kurdish-backed political party, the Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP), threatened the Islamist grip on Turkey and redrew the political map of the Turkish society. But, as the existence of a Kurdish project for territorial autonomy has no place within the Turkish political imaginary, a real dialogue between the Kurdish community and Ankara eventually failed and the war between the Turkish State and the Kurdish “terrorists” retook its bloody course.

As the history of the modern nationalism suggests, the establishment of a “national” government within a part of the “national territory” will be, sooner or later, just a first phase of the nationalist struggle for an independent state. In this context, the Turkish State, which was naturally not very pleased to find some Kurdish autonomous structures at its southern borders, in Syria and Iraq, has chosen to deal with the external “Kurdish question” in a very hawkish way. In July 2015, in order to fight the Kurdish and Islamist terrorism, Turkey launched a large military operation against the PKK and the DAESH in Syria and Iraq, which caused a new conflict between the Turkish State and the main Kurdish organizations. In a short time, the peace became history and the project of an independent Kurdistan ceased to be just a romantic dream...

The Turkish intervention in Northern Syria (Summer 2016) confirmed the inflexible position of the Turkish government. As the existence of a Kurdish autonomous entity in Syria is seen as a real danger by the Turkish State, Turkey tried to avoid the creation of a contiguous Kurdish State along the Turkish-Syrian border. The operation succeeded in Syria, but the Erdogan Administration had to identify soon a new ‘danger’ in Northern Iraq, where the Iraqi Kurdish Regional Government(KRG), controlled by Kurdish pro-independence parties, sets the date for an independence referendum on September 25, 2017. A ‘grave mistake’ for Turkey and an ‘illegal act’ for the Iraqi government, the controversial referendum on Kurdish independence could have been the beginning of a new era in the history of the Kurdish nationalism...

A century after the Paris Peace Conference, the situation has radically changed in 2017 with the pro-independence victory in the September referendum on Iraqi Kurdish self-determination. Unfortunately for the Kurdish nationalists, it was an ephemeral victory. Rejected by the Iraqi federal government, the referendum did not trigger the start of a new state building in Iraq and the Kurdish dream for independence seems to remain a dream for a very long time...

Two years later, on October 9, 2019, the Turkish Army launched the Operation ‘Peace Spring’, an operation intended to destroy the Kurdish autonomous entity in Northeastern Syria. Strangely enough, if Mr. Erdogan was proposing a 30 km-deep safe zone along the frontier, his Minister of Foreign Affairs was talking about the Euphrates River, with Ar-Raqqah and Dayr az-Zawr, as the Southern limit of the Turkish protectorate. This limit was in fact very close to the border set by the National Oath, a century ago. With the Syrian Kurdistan reduced to a helpless entity, Mr. Erdogan was trying to succeed there where Mustafa Kemal failed and to obtain a new Southern borderline, but it seems that he has to wait for better days..

*

The Kurdish nation originated from the ancient communities indigenous to the Mesopotamia and Western Iran. A predominant Muslim people, the Kurds speak a Northwestern Iranian language and are concentrated today mostly in the Eastern Turkey, Northern Iraq and Syria, Western and Northeastern Iran, with smaller enclaves lying within the present-day borders of Armenia, Azerbaijan and Turkmenistan, and a large diaspora in Western Europe.

Website Migration Notice

Our website is being upgraded!

We're pleased to announce that our site is being optimized for better compatibility across all devices and platforms. During this transition period (October 14-30), you will be gradually redirected to new page addresses. Please note that the previous version of the site will no longer be available after November 1st. We apologize for any temporary disruptions you may experience during this migration. Thank you for your patience and understanding as we work to improve your browsing experience.

A Story in Seven Maps by Cristian Ionita